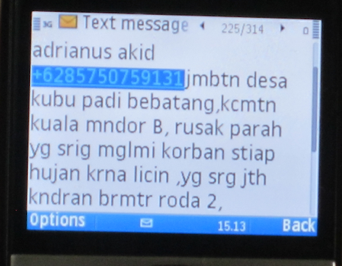

On the same day, after the message was confirmed, RuaiSMS blasted the news by cell phone to 250 people – government officials, activists, mainstream media and tribals – who subscribe to the mobile news service. As part of my work as a Knight International Journalism Fellow I helped launch the service just five months ago to help give rural communities a voice in mainstream news. The SMS news also appeared in a news ticker on Ruai TV’s screen and was posted to the Ruai TV website.

The bridge had been damaged about a year, and the government had never repaired it. But, just days after the SMS news was published, the local government began repairs.

Abet Nego and Adrianus Adam Tekot, two other citizen journalists in Sungai Enau who are also farmers, said before joining the training workshop on citizen journalism they felt ignored, as if they did not exist in the eyes of civil servants. But now that they have been trained and know how to use RuaiSMS to report news that is important to them, civil servants in nearby villages have paid more attention to them.

Another example: Citizens trying to renew their government IDs had to wait for hours to be served. Most of the time, government workers started the ID renewal service at 11 a.m. – but citizens had been waiting since 8 a.m. After Abet Nego sent a message to RuaiSMS, the service began starting at 8 a.m.

These cases have shown how the practice of citizen journalism benefits citizens. To get the benefits, citizen journalists have to know what they should report and that they should only report facts. A 2010 study entitled “Citizen Journalism and Democracy in Africa,” by Dr. Fackson Banda says the practice of citizen journalism should advance aspects of democratic citizenship, including: a) ownership of communication channels; b) civic participation; c) power to hold public officials to transparency and accountability; d) access and accessibility; e) deliberation or thoughtful debate among citizens; f) decision-making or action by citizens; and g) interactivity.

Before RuaiSMS launched on October 10, 2011, Adrianus Akid, Abet Nego, Adrianus Adam Tekot and the indigenous people of Sungai Enau had no access to news or important information, and they never had a way to report any broken bridges or roads. Now, through RuaiSMS, they have access to important news directly using their cell phones.

RuaiSMS has brought access and accessibility for community members, and has opened the opportunity for them to participate in determining their fates. News published in RuaiSMS has empowered Akid, Nego, Tekot and other citizen journalists to hold civil servants to be transparent and accountable for their actions.

Without RuaiSMS, indigenous people in Sungai Enau could not change their villages into better places. The trained citizen journalists have taken on the media role as a new breed of watchdog, watching and reporting the actions of civil servants and companies in their communities in a way that they never imagined before.