Before Peru had even finished testing the COVID-19 vaccine offered by Chinese drugmaker Sinopharm, a network of 487 people received preferential access to the immunizations — all in secret, all connected to government officials.

The distribution of these doses was kept from the public until this past February, when former president Martín Vizcarra — removed by Peru’s Congress in 2020 — acknowledged he had received the shot while still in office. The scandal spread far and wide, and more than 40 government officials resigned as a result.

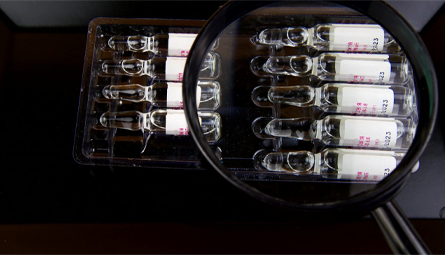

When Peru’s Congress received access to the full list of those secretly vaccinated, the investigative health site Salud con Lupa (in English, “Health Under a Magnifying Glass”) delved deeper. Many names sounded familiar to the journalists working for the outlet. “We knew many of these people even from before the scandal broke out. They were sources to many journalists. They were thought leaders and medical advisors in the Peruvian media,” ICFJ Knight Fellow Fabiola Torres said in an interview with IJNet.

Torres founded the investigative health website Salud con Lupa as part of her ICFJ Knight Fellowship just before the pandemic broke out. With help from ICFJ, she created a network of “Lupa Fellows” to dig into life-or-death health issues across the region. As the pandemic took hold across Latin America, the website became a vital source of accurate news in a sea of disinformation, its stories leading to the dismissal of corrupt officials, the removal of unproven drugs from approved COVID-19 treatments, and more.

“With the support of ICFJ’s Knight Fellowships, I was able to develop a solid approach to covering health,” Torres said. “This was crucial in reporting on the pandemic because our focus on investigations and useful news to help people in a health crisis was really different from other outlets. We have been able to innovate the ecosystem of journalism specialized in science and health.”

Investigating Peru’s vaccine scandal, the Salud con Lupa team recognized the names of what Torres referred to as “the Peruvian scientific elite,” in addition to politicians and academics from top universities in the country. The journalists set out to identify the ministers, government officials, researchers, diplomats and businesspeople involved. Two months later, they published the results of their investigation, titled “Vacunagate” (in English, “Vaccinegate”), and mapped the whole network of those who received the secret shots.

Through extensive data analysis and 23 published articles, the project showed the relationships among the power players involved, and how they benefited their own families and colleagues. “We established the connections among everyone who had received the vaccine in a secret way,” Torres explained.

The team also tracked $800,000 in donations from Sinopharm to the Peruvian Health Ministry while the country was still negotiating the purchase of the vaccines.

Donations to the Health Ministry aren’t inherently illegal in Peru, but Salud con Lupa reporters noted how timely these “gifts” were. “The State hadn’t yet closed a deal with Sinopharm to purchase vaccines against COVID-19 at the time. In fact, it was right in the middle of negotiating with Pfizer and AstraZeneca — negotiations that would stop months after,” the Salud con Lupa article explains.

Peru’s Sinopharm vaccine trial — the largest in Latin America — is now surrounded by allegations of irregularities. The country’s anti-corruption office has launched an investigation that will continue until October. While the probe continues, the Peruvian Congress has already concluded that there was a “strategy” to benefit Sinopharm. It also banned former president Vizcarra from holding public office for 10 years.

Salud con Lupa didn’t just report on Vacunagate as the political scandal it was. The outlet also focused on the bioethical questions their investigation raised. “This is a corruption case, and it’s also a scientific scandal that reveals the conflicts of interest that were normalized by many scientific community members in Peru,” Torres said. “That also affected the public’s trust in how the vaccine was tested and researched.”

Photo Credits: Salud con Lupa