The International Center for Journalists (ICFJ) is connecting journalists with health experts and newsroom leaders through a webinar series on COVID-19. The series is part of our ICFJ Global Health Crisis Reporting Forum — a project with our International Journalists’ Network (IJNet).

This article contains mentions of suicide.

The World Health Organization estimates that suicide is the cause of more than 700,000 deaths annually. Of these, over three in four occur in low- and middle-income countries.

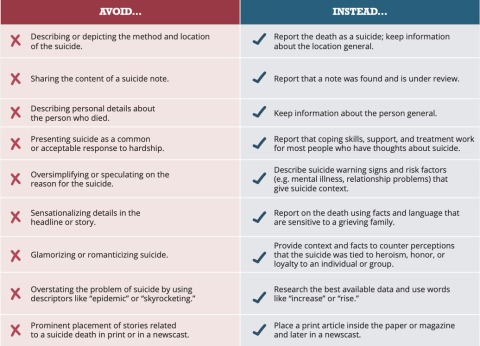

In news coverage, there is worrying evidence that irresponsible reporting can lead to imitation suicides, said Klaudia Jázwińska, a journalist and researcher who analyzed articles from major news outlets on the passing of Dr. Lorna M. Breen to see how closely they adhered to suicide reporting guidelines.

Jázwińska was joined by J. Corey Feist, the co-founder of the Dr. Lorna Breen Heroes’ Foundation, Dr. Victor Schwartz, the CEO and director of the mental health support organization Mind Strategies, and Lorna Fraser, the executive lead at Samaritans’ Media Advisory Service during a recent ICFJ Global Health Reporting Forum webinar for a discussion on how journalists can best report on mental health and suicide.

“Everything that is a natural impulse for journalists when reporting a story is problematic when reporting on suicide,” said Schwartz. He explained that journalists should avoid identification, creating a narrative, and relatable and emotionally compelling angles in their reporting on the issue: “You don’t want to make the person heroic.”

Respecting the family

Dr. Lorna Breen, after whom the Dr. Lorna Breen Heroes’ Foundation is named, was the head of emergency at New York Presbyterian Allen Hospital. During the pandemic, she, like many other healthcare professionals, feared losing her medical license if she sought psychiatric help. "[She was] overwhelmed, but [there was] stigma associated with taking a break,” said Feist. Dr. Breen later lost her life to suicide.

While her family was coming to terms with her suicide, media coverage was overwhelming, and it failed to consider their feelings and privacy, said Feist. When Breen’s story became sensationalized, her family decided to tell it on their own terms: They created the Dr. Lorna Breen Heroes’ Foundation to advocate for the mental health of healthcare workers.

Though far from perfect, past reporting has spurred important conversations around how to have sensitive discussions about mental health and suicides in the U.S., said Schwartz. He further stressed that it is important to respect the sensitivities of family members when reporting on suicide.

[View past webinars and key quotes]

The public health element

The risk of contagion, or imitation, suicides can be a consequence of sensationalized and irresponsible reporting, said Schwartz and Jázwińska. There was a 10% increase in suicides after the death of actor and comedian Robin Williams, for instance, due in part to the nature of the news coverage that followed, said Jázwińska.

Fraser explained that six decades of research shows links between certain elements of media coverage and suicide rates. This includes reporting that goes into detail about how the suicide happened, for instance. “How this comes about is through social learning. People who are more vulnerable to the effect are people who struggle with their mental health — people who are bereaved, particularly those who are bereaved by suicide and young people,” she said. “[They] over-identify with certain characteristics and circumstances, and may start to feel that [suicide] is a suitable option for them.”

Panelists mentioned the “Papageno effect,” which ties hopeful stories of handling times of crisis to falls in suicide rates: When covering suicide, journalists should instead focus on how people can seek help, resources and information about coping skills, they said.

“As long as [the reporting] is done responsibly and sensitively, the media can be a real force for good,” urged Fraser. “Being aware of media guidelines will really help you make sure your reports are as safe as possible.”

Suicide is preventable

Suicide can be prevented, said Jázwińska and Schwartz. “If you portray suicide as simple or inevitable, or as a crisis or epidemic, that’s an issue,” explained Schwartz.

Suicide rates decreased slightly in the U.S. in 2020 during the pandemic, though they have increased among essential workers. There is also a blurred line between the symptoms of stress and anxiety and depression, added Schwartz.

“If someone is suicidal, that is often a temporary state. If they are given the resources, they will not follow down that path. Journalists are in a position to amplify positive messages and avoid repeating [reporting mistakes] in the future,” said Jázwińska.

If you've found this content distressing or difficult to discuss, you're not alone. There are resources available to help. Start by exploring the resources from the Dart Center for Journalism and Trauma, and please seek psychological support if needed.