Srishti Jaswal grew up in a small rural town in the Himalayas where there were no news outlets and no reporters. “In my entire life, nobody had ever seen a journalist before,” she says of her hometown in northern India. “We didn’t even know what journalism was.”

Today, Jaswal is an award-winning journalist, reporting on controversial issues such as ritual killings despite receiving threats herself – all too common for women journalists in India. She is also a proud member of ICFJ’s global network of journalists, having benefited from ICFJ resources and training.

Jaswal is one among the tens of thousands in ICFJ’s network doing vital and sometimes dangerous work. She was lucky that an observant teacher in her village recognized her potential, gave her out-of-town newspapers to read, and suggested she consider a career in journalism. Now, she’s doing amazing stories like these:

- An exposé of a national food distribution system that left out millions of needy families

- A story about starvation deaths that were not officially recorded, a piece that earned her a “best emerging journalist” award from the European Commission

- And an investigative report about ritual killings linked to religious superstition in tribal areas, produced with the support of the Pulitzer Center

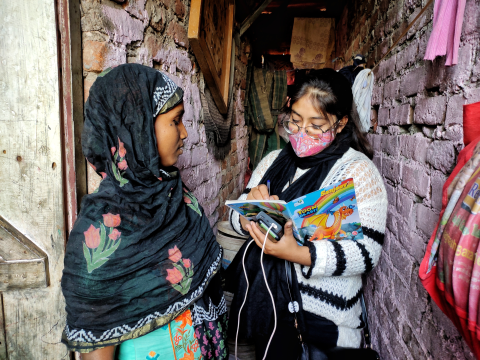

Currently a freelance journalist whose stories have appeared in international outlets including Al Jazeera and VICE, Jaswal is also an ICFJ nutrition reporting fellow working on stories about malnutrition and neglect. She learned about the fellowship as an avid reader of ICFJ’s International Journalists’ Network (IJNet).

Like Jaswal, U.S. journalist Anna Catherine Brigida is driven to tell stories of people who are marginalized by poverty and discrimination.

In 2020, she was chosen for a fellowship offered by ICFJ and its partner, the Border Center for Journalists and Bloggers, aimed at giving U.S. journalists a chance to report on issues that span the U.S.-Mexico border. Her stories focused on the suffering of thousands of immigrants who fled violence and poverty in Central America only to die in immigration detention centers along the border. “The opportunity for me to go to the border and see immigration from a different side was so illuminating.”

Brigida’s stories have appeared in major international outlets like The Washington Post, the Los Angeles Times and The Guardian of London. ”People come down from New York when there are big cases, but I’m able to keep up with the story longer and add to the conversation,” she told us.

At the award-winning media start-up Coda Story in Georgia, editor and co-founder Natalia Antelava leads a team of journalists who have spent the past few years covering root causes of the war in Ukraine and other Russian incursions.

“We are a different kind of newsroom,” she said. “Our mission is to enhance public understanding of crises by explaining undercurrents that run through them.” For instance, Coda has covered such critical stories as Putin’s plans to create a new Russian empire, and what the cult of Stalin in Russia has to do with the war in Ukraine.

“We all know, crises don’t end when news crews leave,” said Antelava. “This is the kind of journalism that we are determined to carry on doing now, as new patterns and undercurrents emerge from the rubble of Ukrainian cities and the new waves of unprecedented oppression in Russia.”

Like Jaswal and Brigida, Antelava and her team are producing journalism that matters to their communities and the world.