There is nothing like interviewing women with fistula to realize, in your heart and in your bones, what fistula does to women: the humiliation, marginalization, loss of self-esteem, and depression. Fistula is an orifice resulting from ruptured tissue between bladder, rectum and vagina that provokes permanent incontinence. Feces and urine flow through the vagina.

Obstetric fistula is caused by early and repeated pregnancies, long and complicated deliveries without proper medical care, delays in reaching hospital, clandestine abortion and violent rape. Embarrassed by incontinence and bad smell, shunned by family, friends and neighbors, rural women cannot fetch water, go to the market or work in the fields. They can’t take public transport, even leave the house. Many are banished to huts in the village outskirts. They eat less and become anemic and malnourished.

Some quick facts:

- Some 100,000 women need surgery for obstetric fistula in Mozambique but operating capacity is under 1,000 a year.

- The rate of occurrence is three or four fistulas developed per 1,000 births. Annual births in Mozambique: 900,000.

- Just over half of births take place with qualified medical staff.

- Forty per cent of girls aged 15-19 are married or cohabit.

- Of the married girls, 22% have an age difference of ten years or more with the husband - likely to be child brides.

View our slideshow that helps put a face on some of the victims of this condition. Below are some of the heartbreaking personal stories we heard at Maputo Central Hospital from women waiting to have the surgery that will restore their health and their dignity:

Zelia Matimbe, 22 (in slideshow, with abdominal scar):

An orphan, she never knew her father. Her mother died when she was in grade 3, and her death stopped Zelia’s schooling. She had first child at 14, the second at 18. Urine and feces started flowing from her vagina after the second baby. She was very sick. “My body was hot, my legs hurt, I could not walk,” she says.

Her husband ignored her. He took a second, younger wife and took both children with him. Zelia’s younger brother cared for her, bathed her and fed her. One day when the pain was unbearable, Zelia crawled to the health post. She was transferred to Maputo, 1,000 kms away, where she was operated for a double vaginal-rectal fistula in 2010.

She happily reports that she is not incontinent any more but the wound has not healed and she is back at Maputo’s Central Hospital.

Ana Fernando, 22 (in slideshow, with pillow):

Diagnosed with complex bladder/vaginal fistula, Ana says, “My baby died during delivery, which lasted two days. I did not even see his face. I was 17 and never attended school. Two weeks after delivery, urine was flowing freely, unstoppably. I went to the local health post, then was transferred to the rural hospital in Chicuque, then to the provincial hospital in Inhambane and then to Maputo.

I had the first operation in 2010 and I need another. I am lucky: my mother and my boyfriend support me. Once cured, I will be able to go fetch water with other women without problems or harassment and will be able to live with my family and community.”

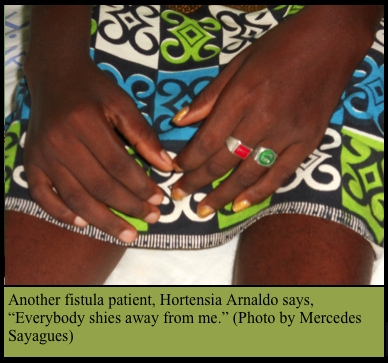

Hortencia Arnaldo, 25 (in slideshow, photo of her hands only):

“I am from Zavala, Inhambane, and had my first baby aged 17. The birth was long and complicated and the baby was born dead. When I started urinating without control, my boyfriend left me and found another woman. I had friends but no longer. Everybody flees from me. They point at me in the street and say: ‘She wees in bed, she is not a woman, she is nothing.’”

“I rarely leave my house. To travel, I use bundles of old cloth as pads. But I know I will get better. I had one surgery, am waiting for the second. I quit school when I got pregnant, I did not finish primary school. When I get better, I would like to go back to school and study to be a policewoman. That is my dream.”

S.F., 15

S.F. was 14 when she was married to a miner, who promptly made her pregnant and went back to South Africa, leaving S.F. with his other, older wives in a rural area. Labour was complicated. After 24 hours, the traditional midwife recommended the girl should go to a health post – 12 hours away on an ox-driven cart. At the health post, the nurse summoned an ambulance from the provincial hospital. It arrived 24 hours later. At the hospital SF had a caesarean – 72 hours after starting labour. Ten days later she started urinating trough the vagina but the nurses told her it was normal and sent her home.

When her husband returned, he accused her of killing the baby and not being a proper woman, and chased her away. Her family could not take her back because they could repay the lobolo, or dowry. Suffering from fecal and urinary incontinence, S.F. lived in an isolated hut at the outskirt of the village. She begged for a living.

One day she heard that she could be cured in Maputo, 700 kms away. She sold her few possessions, saved the alms and boarded a bus to Maputo Central Hospital. She was so undernourished she had to wait three months at the urology ward to recover weight before surgery. She has recovered well and hopes to rebuild her life.