When Zimbabwe held its long-awaited presidential election earlier this year, a group of fact-checkers were ready to track fake news and misinformation spread on social media and elsewhere during the tense voting to replace Robert Mugabe.

The Centre for Innovation and Technology (CITE), a Bulawayo-based innovation hub, had collaborated with Code for Africa and PesaCheck - partners of the International Center for Journalists (ICFJ) - to conduct a series of trainings on spotting and debunking misinformation online.

Armed with this training, CITE set up a verification team with ZimFact, a fact-checking organization based in Harare. Their goal was to identify and check claims posted on social media during the campaign period, on election day and after the elections.

Zimbabwe had long been known for violence and voter suppression during elections; this poll was the first real test of whether technology would be used to suppress voters in the new post-Mugabe era. And whether it could be used to counter voter suppression.

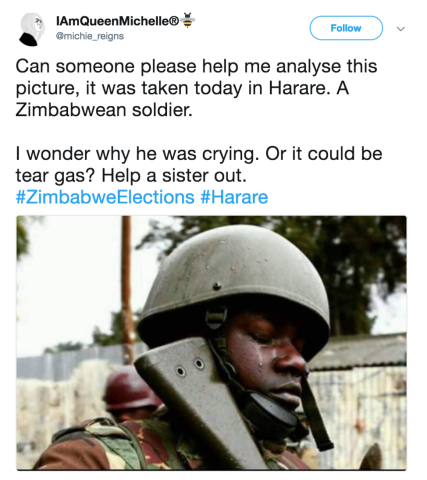

We identified nearly 80 claims posted on social media during and after election day. We found that one-third of the claims we tracked were false, and another one-third were verified as true. The rest we found to be either misleading or inconclusive, meaning that there wasn’t enough information to determine the accuracy of the claims.

Claims verified on election day revolved around voter turnout and intimidation. One notable claim was linked to speculation on social media that a polling station in a Bulawayo suburb was designated only for military servicemen - and that civilians and observers were not allowed to access it. Additionally, the presiding officers were alleged to be military officials, meaning that there was no independent oversight.

We flagged this tweet, and our team got down to fact-checking the claim after doing some physical verification with the assistance of the election observers on the ground. We found out that the alleged polling station at the shopping center, did not exist and there were no military servicemen there.

Although the shopping center is close to the army barracks, our investigation showed that there were two polling stations near the location, and army personnel were voting alongside civilians at these two stations without incident. We flagged the incident as “false.”

On election day, we also tracked a video reportedly showing the main opposition presidential candidate receiving money from former first lady Grace Mugabe in a South African hotel room. In addition, we looked into a newspaper report claiming that people with ‘fake nails’ would not be allowed to vote. These were also found to be false.

As part of our verification process, our team used Check, a collaborative fact-checking platform developed by Meedan. The tool has been used for similar election verification initiatives in the United States, France and Kenya.

We looked for claims that we could verify, and we also asked members of the public to submit any content that they would like checked.

We worked with journalists to verify content such as photos and videos posted online using a combination of online tools and observers on the ground.

Our team used a six-step process that established the source of the reports, the place of occurrence, type of violation, corroborating content from other sources, and the authenticity of any media shared with the report.

The verified or debunked claims were then posted back on various social media platforms, often in response to the misleading content. That way the chances of this misinformation spreading were greatly reduced.

With social media becoming increasingly important in Zimbabwe, misinformation can easily bypass the safeguards that previously existed with mainstream media, and it is now much easier to spread falsehoods than ever before.

Our verification exercise showed that fact-checking can be an important tool during elections, and that the public can play a part in sharing accurate and verified information to fight against misinformation.