Astudestra Ajengrastri, a Jakarta-based TruthBuzz Fellow with the International Center for Journalists (ICFJ), has the difficult task of countering the plague of disinformation on social media in Indonesia. In the runup to the country’s presidential elections in April, she faced a particularly big challenge: a convincing audio message went viral on WhatsApp claiming that millions of fake ballots were about to be cast in favor of the incumbent president.

This was the first time that disinformation about the election spread in the form of a voice memo, Ajengrastri said. It took off. The message ranked as one of the top three most shared examples of disinformation in Indonesia in January, with 53,000 conversations about the rumor posted online by the end of the month, according to the local monitoring agency PoliticaWave.

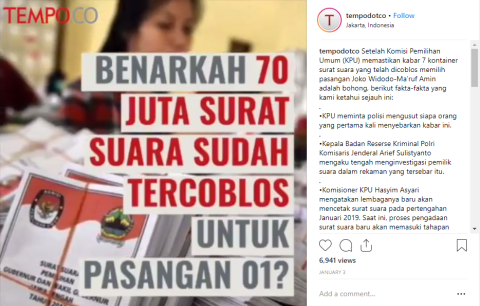

“It was alarming,” said Ajengrastri, because the recording seemed so authentic. The WhatsApp “voice note” appeared to be a man, talking on a phone, about the recent arrival from China of 70 million fake ballots for the incumbent. “Disinformation can now spread in all kinds of forms,” she said. “We were just talking about images and videos, and now voice notes?”

Ajengrastri jumped into gear at Tempo Media Group. The news outlet had reported on the recording and its immediate debunking by the election commission, but found that false rumors were still spreading online. With Ajengrasti’s help, Tempo spread the word in an innovative way: Instead of simply publishing text stories, Ajengrastri quickly pulled highlights of the reporting into a video that now has been viewed across Tempo’s social media accounts more than 7,000 times.

Indonesia is far from the only country where disinformation spreads by bogus audio recordings. The interim head of Poynter’s International Fact-Checking Network, Daniel Funke, has called fake audio messages the next misinformation format, highlighting hoaxes that went viral in Argentina, Mexico and India. “This hoax was part of a sophisticated propaganda campaign,” Ajengrastri said. “That’s incredibly hard to combat.”

This was also an issue during Brazil’s recent election, said Sérgio Spagnuolo, ICFJ’s TruthBuzz Fellow in the country. “People tend to believe slightly more in oral accounts,” he said, “especially because this type of content is spread through a network of friends, family members and acquaintances, which helps create a sense of trust in the messages.”

As a Fellow, Spagnuolo is working with fact-checking startup Aos Fatos to counter this trend, in part by finding ways to share verified information via voice memos. “It’s a hard thing to do consistently,” he said. Other Fellows are amplifying his fact-checking efforts in India, Nigeria and the United States. They are building new storytelling formats and engagement strategies for local newsrooms.

With the election only weeks away in Indonesia, disinformation continues to fuel political polarization, Ajengrastri said. Police arrested several people for their alleged involvement with the hoax, while journalists like Ajengrastri and the team at Tempo do their best to counter the explosion of new formats for false information on social media.

ICFJ’s TruthBuzz Fellowship is supported by Craig Newmark Philanthropies.

Photo Credit: Tempo