This article was first published on IJNet. Mattia Peretti is a 2024 ICFJ Knight Fellow.

If you work in journalism, you might recognize that 2024 was a year of reckoning for our industry. I certainly do.

At the start of the year, I embarked on a Knight Fellowship with ICFJ to explore how generative AI can be used to improve the way we serve information to our audiences. I was determined to do something meaningful.

But something sounded off-key.

I wanted to make sure I knew what I was doing and why I was doing it. Imagine how stupid I felt when I realized I had embarked on the fellowship with a bag full of assumptions, failing to reflect on what the industry actually needed, and the arrogance to assume that since I had become some sort of AI expert over the previous years, obviously AI had to be part of the solution I was going to bring to the table. It took me a while to understand how that was not even the main flaw of my problem statement. Only after a few months of deep conversations within the News Alchemists community I was able to understand that “serving information to audiences” is a deeply flawed way to describe the mission of journalism, and one that actively hinders our ability to play a meaningful role in people’s lives.

And it appears that many other people across the industry had the same realization.

[Read more: Reinventing journalism: New ideas for a people-centric sustainable future]

Why do we, as journalists, do what we do?

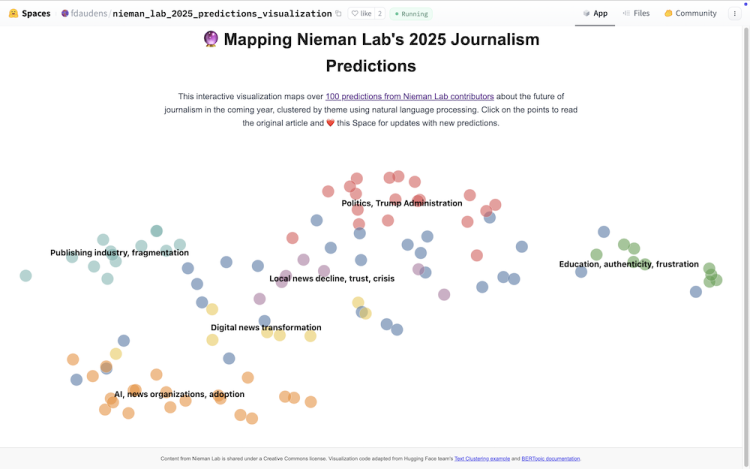

Take the predictions for 2025 that Nieman Lab published in December. Analyzing the main themes covered in them, Florent Daudens noticed something interesting: “Plenty of AI and U.S. politics (surprise!), but there’s also this horizontal axis spanning industry strategies to deep reflections on how to engage with the public”:

The predictions that Florent is referring to (the blue dots on the map) talk about ”rebuilding the bonds between communities and newsrooms” (Sarabeth Berman), “sustaining meaningful relationships” (Adam Thomas), “ensur[ing] we can be helpful to our communities” (Jennifer Brandel), and asking fundamental questions such as “Why do we, as journalists, do what we do? What’s our fundamental value?” (Anita Li).

That these reflections are so prominent in what people across the industry have on their minds at the dawn of 2025 is an incredibly encouraging sign. The reason I believe that we must stop thinking of our mission as “serving information to audiences” is exactly in line with what all these predictions are getting at: it’s time to fundamentally rethink and redefine our relationship with audiences and our role in society.

What does it mean to listen to your audience?

It’s fairly common to hear calls for newsrooms to “listen to their audience,” and the idea that there’s merit to that suggestion seems to be well established. Yet I still notice resistance, which manifests itself mostly in two ways: first, in the undying argument that if we listen to audiences and give them what they want we will end up publishing only cat videos; second, and more subtly, in the mindless production of content that fills websites and collects page views but leaves people with no support in understanding why the information they’ve been provided should matter for their lives.

In response to the cat videos argument, let’s get this out of the way: listening to your audience does not mean abdicating your responsibility as a journalist; it does not mean just doing what they want you to do. Listening means making sure that your audience feels heard in your editorial decisions. It doesn’t mean losing track of your values or of your journalistic mission: helping people navigate their lives and providing them with the information and the context they need to meaningfully participate in their communities.

Think of your journalism organization as a restaurant. People can’t just walk in and ask for whatever they want to eat. You are in charge of the menu — which you can change, but not too often or your customers won’t know what you’re about anymore. You can combine healthy options that are good for them with yummy treats that might have too many calories but put a smile on people’s faces. Setting the menu is your responsibility, and your privilege. Listening to your audience will help you present options they actually want, and build a relationship with loyal customers who will come back to your restaurant because they trust you to curate a menu that is good for them.

Another way to look at how, in practice, we can balance the needs of audiences with our journalistic mission is represented by how Schibsted Media Group approaches personalization. Homepages are highly personalized, with most spots optimized for engagement by showing stories that are relevant for the individual user. But Schibsted aims to “strike a balance between the stories everyone should know and ones that are of particular interest to specific users,” so they reserve some of the top spots for “stories that help promote Schibsted’s journalistic mission, and put those up despite how they perform.”

[Read more: The future of news and the promise of community-centered journalism]

From listening to conversation

Once we’ve agreed on the importance of listening to your audience, we must move to the next level: don’t just listen — have a conversation with them.

Too often, when newsrooms practice listening, information stops after flowing one way. We ask people for their ideas and opinions to get the insights we need for content or a project, and that makes us feel like we’re listening. But if the conversation ends there, and we don’t let audiences know what we do with the information they have generously provided, that won’t do much to build trust and accountability.

Real listening and conversation means being transparent about the choices you make as a result of the listening process. It means acknowledging mistakes and correcting them; it means accepting that some people in your audience will always know more than you about any given topic — and you can ask for their help; it means being open, showing how journalism is done, and even sharing the difficult choices you make on a daily basis, rather than just giving people the final product and expecting them to automatically trust you.

Making sense of the world, together

Let’s go one step further: I would argue that healing our relationship with the people we aim to serve requires us to stop thinking of us (working in journalism) and them (the audiences) as two different breeds. Journalism might be a job for us and not for them; but journalism, intended as the process of making sense of the world through information, is a collaborative effort we are all taking part in. We are all human beings trying to understand the world — together.

Add to that that we often forget that each one of us working in journalism is also someone else’s audience. Our news consumption might not be representative because we are so immersed in this journalism thing day in and day out, but that doesn’t mean we should forget to bring our insights as readers and users into our work.

Some newsrooms understand that so well that they made this part of their editorial strategy: readers of Il Post (an Italian digital media founded in 2010) have heard the editorial team sharing multiple times that one of their criteria for deciding which less newsy stories to write about is simple: if someone in the newsroom is curious or passionate about a story, it’s likely their readers might find it interesting too. Il Post has no paywall and started a membership program in 2019: by the end of 2023, 75% of their revenue came from membership. This editorial strategy appears to be working. (Full disclosure: I’m a member and a big fan of their work.)

But back to the audience side of things: let’s mind our language. Over the last few months, at various industry conferences as well as on social media, I started paying attention to how we talk about the people we aim to serve with our journalism, and I found myself feeling quite uncomfortable and even a little... cringe.

We refer to audiences as eyeballs, credit cards, numbers. Rarely as people with problems and needs that is our mission to help and meet. Our obsession with page views and engagement — justified in its essence but not in how it translates into practice — leads us to dehumanize the audience, making it harder to find optimism and motivation in our sense of purpose.

I don’t mean to suggest this as a silver bullet — spoiler alert: there is no silver bullet — but I strongly believe there’s one thing we must be doing much more often to counter this trend toward dehumanization: meet our audiences in real life.

The good news is that this is already happening. Many brands organize events, live shows, think-ins, and other occasions to meet face to face the people they work for. We must double down on that. Do it more often and as a core element of our activities, and not as a nice-to-have. In 2025, people crave connection, relationship, community and conversation. They want to feel part of something. What better way do we have to achieve that?

Focus on what our real purpose is

After a long list of “we must do” and “we must change,” I feel like it’s time to acknowledge the elephant in the room: change is hard. And working in journalism is often… well, not easy, to say the least.

That’s exactly why I believe we should continue building spaces and support groups where we can feel “less alone in the big fight,” as one of my News Alchemists friends put it. Working on changing journalism and redefining the relationship with our audiences requires serious and difficult conversations, but we can design joyful processes to guide us through them. We can be playful and continue bringing hope to the table as we shape our future, whether within our teams or with the products and experiences we create.

I also want us all to embrace what Candice Fortman wrote in an incredible post on LinkedIn a few weeks ago: “Saving journalism has never been the job.” We can only go through change with hope and a positive attitude, and get out of it healthy and successful, if we free ourselves of the pressure of having an entire industry to save. It’s not journalism that requires our effort and ideas. It’s the people we care for, and the communities we want to support and strengthen. If one day we wake up and journalism is not the best way to help them anymore, so be it. Let’s shed the old skin and find out how beautiful the new skin can be, whatever it looks like.

So let’s stop protecting old ways that don’t work anymore and only exist to guarantee their own survival. Let’s do what we can to help our organizations look more like what we need them to be to serve our mission, but let’s also give ourselves permission to stop working for organizations that just don’t want to change. Let’s encourage each other to recognize when it might just be time to let them go.

I believe that journalism can and will be better. I believe that 2025 can truly be the year when we redefine our relationship with audiences and our role in society. If we continue supporting each other, with passion and care, we can really make a difference and invite more people to join arms with us. Because we all need to be involved. The change we need is systemic and it’s the business of all of us, not just of a few chosen ones with “innovation,” “product” or “leadership” in their job title. So let’s get together. There’s work to do.

What’s next for News Alchemists

The work I started on News Alchemists has not concluded with the end of the fellowship. In 2025, I plan to continue it by:

(1) Consulting for news organizations that want to find new avenues for sustainability by optimizing their mission and value proposition for the concrete value they can offer to their communities.

(2) Continuing to facilitate important conversations about how to put people at the center of our journalism through the News Alchemists community, which is ready to grow from 15 founding members into a bigger group of thinkers and doers from across the information ecosystem.

(3) Writing a weekly newsletter featuring a list of seven things I read that make me think and give me hope: links about changing journalism, and about audience, community and sustainability. (Something that I’ve already been doing on LinkedIn in preparation for starting the newsletter.)

This is a work in progress. But if you’re interested in receiving the newsletter when it starts, and staying informed about other News Alchemists activities, you can leave your email through this form.

Photo by Pablo García Saldaña on Unsplash.